Debunking Reuters’ Story “PBoC Blocked 300-500t Gold Import In 2019”

From analyzing SGE premiums, the gold price and cultural trends, my conclusion is that the PBoC did not block 300-500 tonnes of gold from being imported in 2019, as was reported by Reuters.

Written by Jan Nieuwenhuijs, originally published at Voima Gold Insight.

In August 2019 an article by Reuters—stating the Chinese central bank was firmly cutting off gold supply in the mainland—caused a great stir in the gold community. Unfortunately, many people plainly accepted the story, although it was highly misleading. In today’s article, we will analyze Reuters’ claims, and make sure to eliminate any confusion of what happened in the Chinese gold market.

In my previous post on Shanghai Gold Exchange (SGE) premiums, we saw the Chinese central bank implemented a policy in early 2017, of raising a barrier cost at roughly 0.5% on gold imported into the Chinese domestic market. By comparing premiums on gold traded in the Shanghai Free Trade Zone (SFTZ) versus gold traded in the Chinese domestic market, it appeared that the People’s Bank of China (PBoC) generates an artificial premium. Using a similar approach, allows us to analyze if the PBoC obstructed gold imports in 2019. In my view it was very little. Certainly not 300-500 tonnes, which was the amount reported by Reuters on August 14, 2019. From Reuters:

China has severely restricted imports of gold since May [2019], bullion industry sources with direct knowledge of the matter told Reuters

The world’s second largest economy has cut shipments by some 300-500 tonnes compared with last year

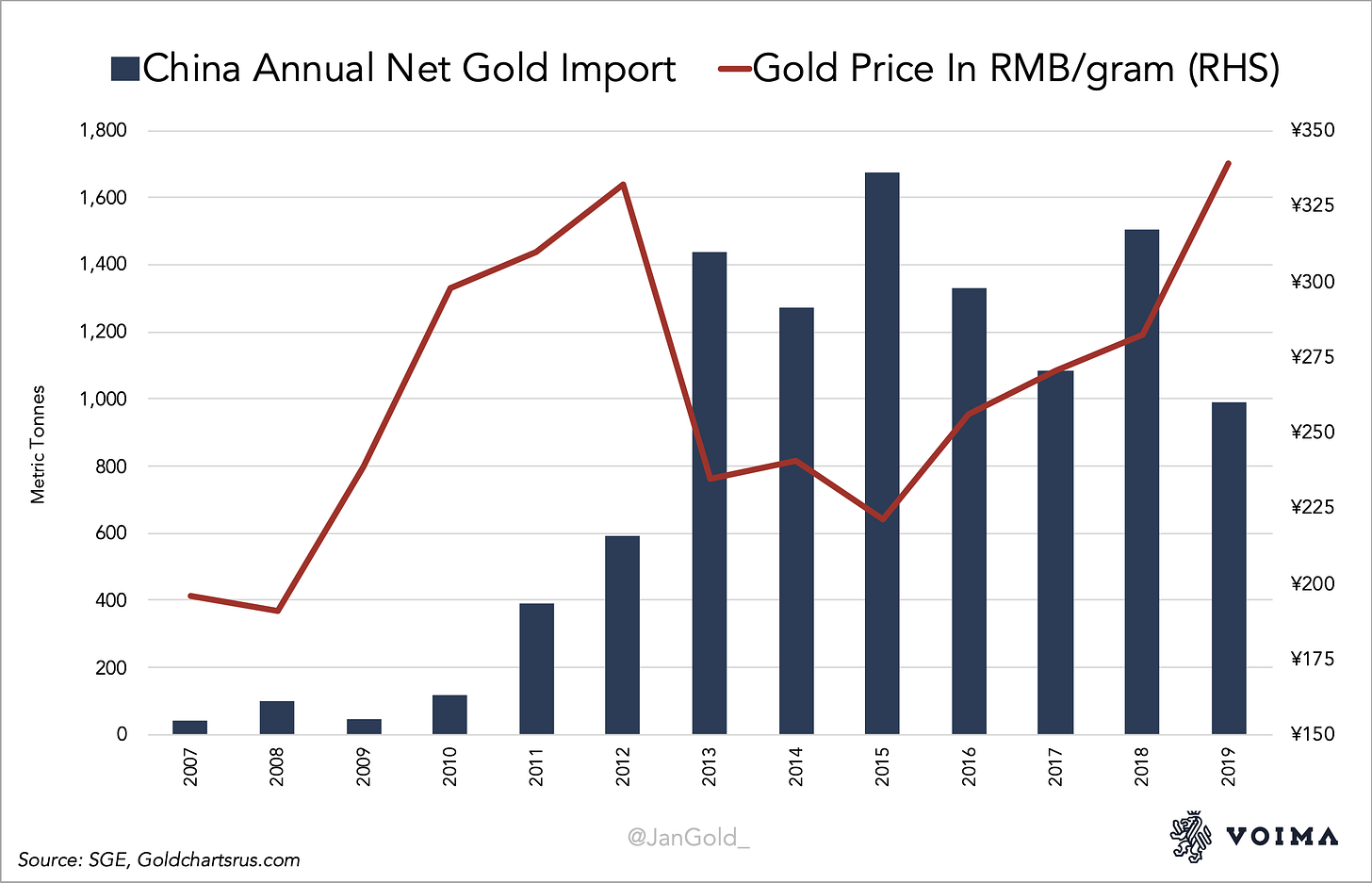

China is the world’s biggest importer of gold, sucking in around 1,500 tonnes of metal worth some $60 billion last year

In May, China imported 71 tonnes, down from 157 tonnes in May 2018. In June, the last month for which data is available, the decline was even sharper, with 57 tonnes shipped compared with 199 tonnes in June last year.

...quotas [PBoC import licenses] have been curtailed or not granted at all for several months, seven sources in the bullion industry in London, Hong Kong, Singapore and China said.

It has also restricted gold import quotas before—most recently in 2016 after the yuan weakened sharply, bullion bankers said.

As I mentioned in my previous post, in 2015 and 2016, the PBoC was defending a weakening renminbi by selling foreign exchange reserves. Late 2016 the PBoC had burned through $1 trillion worth of reserves. At that moment, the PBoC started restricting gold imports, and thus SGE premiums spiked to nearly 4%.

By comparing SGE premiums with Shanghai International Gold Exchange (SGEI, located in the SFTZ) premiums, we saw that when capital outflows declined in 2017, the PBoC continued “soft restrictions” on gold imports. Consequently, since 2017 SGE premiums have, on average, been at or above 0.5%.

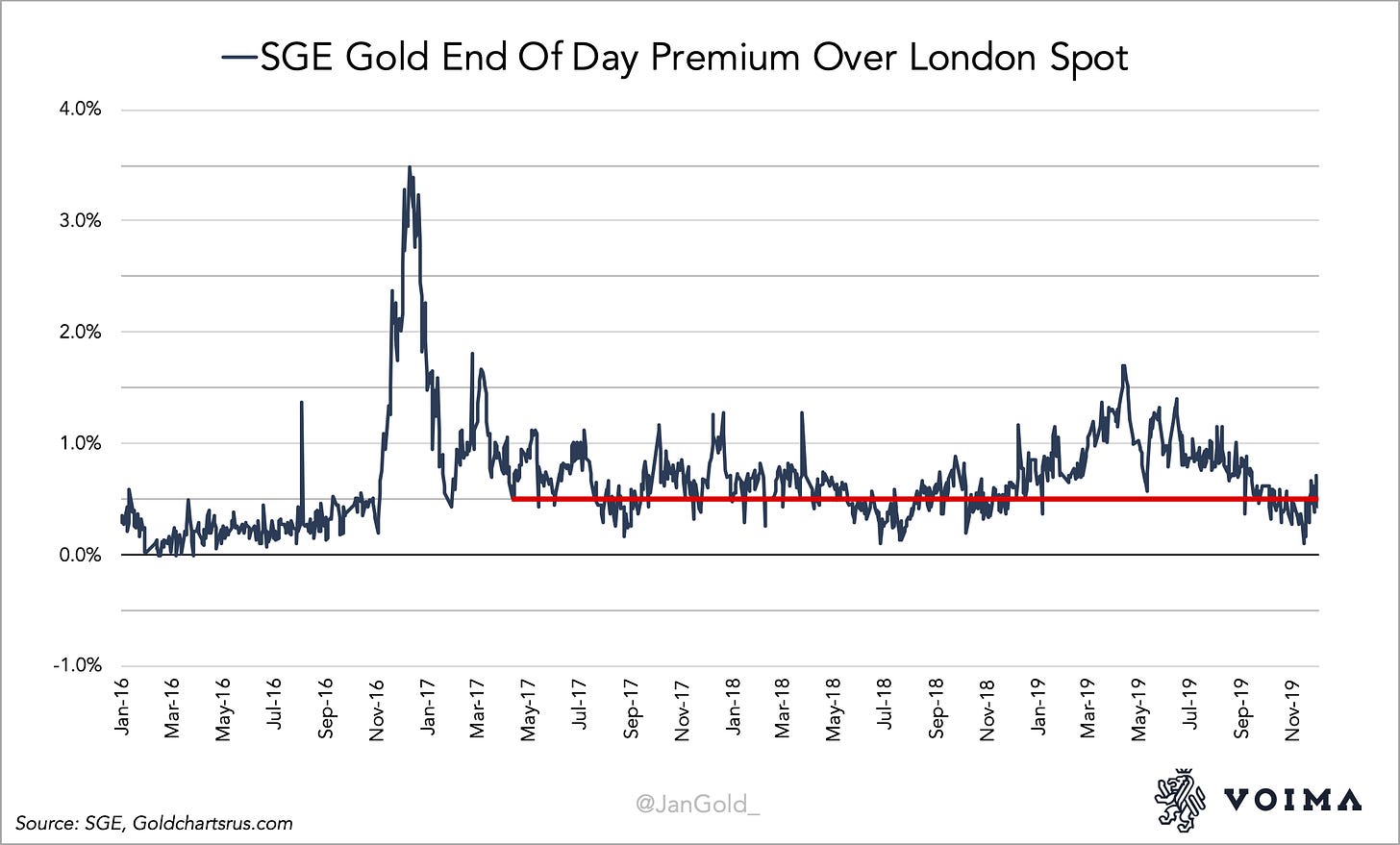

For today’s analysis, let’s start with the following chart: SGE end of day premiums from January 2016 until December 2019 (sourced from the SGE website).

SGE premiums spiked late 2016, after which they fell back to roughly 0.5%, and in 2019 increased somewhat, peaking at 1.5% in April. Effectively, SGE premiums in 2019 were only slightly above their post-2017 average (0.5%), which signals there wasn’t much obstructed from being imported.

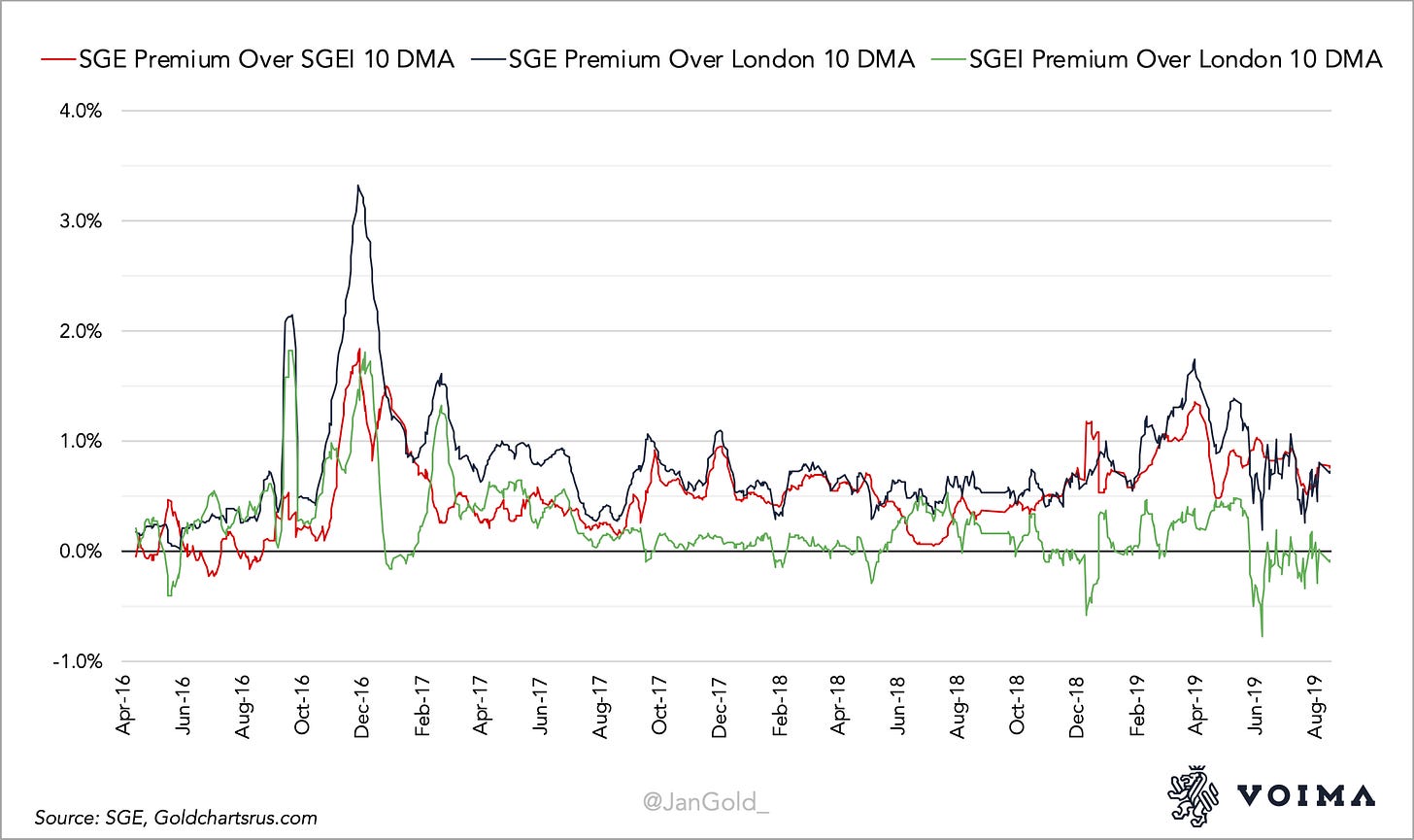

Additionally, if we look at the next chart, we see that in late 2016 the “uncensored version of SGE premiums” (SGEI premiums) initially increased, but were slammed down in November, which is revealed by the red line going up. (The red line is the difference in the price of gold at the SGE and SGEI.) The cause of the difference in price between SGE and SGEI gold was PBoC import restrictions.

Please, also take a look at this chart, with the same parameters, but sourced from a Bloomberg Terminal. Provided by Bron Suchecki from ABC Refinery.

PBoC interference worked because slowly SGEI premiums came down to zero in 2017. Chinese gold demand weakened.

However, in the above chart we can see SGEI premiums didn’t rise in 2019. If gold demand in Shanghai is stronger than in London, this should be reflected as a premium in both the SFTZ (SGEI) and the domestic market (SGE). That the green line hovered around zero while the red line went up in 2019, tells me Chinese demand was not strong. Although, the PBoC did raise the costs of importing metal, evidence suggests little was obstructed from coming in or SGEI premiums would be elevated.

The real reason gold imports collapsed in May 2019 was because the gold price rose. As I have pointed out in my previous post “The West-East Ebb and Flood of Gold,” people in the East buy more when the gold price is falling (or in a steady market) and buy less when the price is rising. Also, they sell when prices peak. This pattern is at least 80 years old.

When the price of gold started climbing in May 2019, the Chinese unsurprisingly halted purchases and imports collapsed. In the chart below we see Chinese monthly gold imports hitting a multiple year low the moment the gold price made multiple year highs. Coincidence? I think not. These are normal and old global gold market dynamics at play.

Reuters wrote on August 14, 2019:

In May [2019], China imported 71 tonnes, down from 157 tonnes in May 2018. In June, the last month for which data is available, the decline was even sharper, with 57 tonnes shipped compared with 199 tonnes in June last year.

quotas [PBoC import licenses] have been curtailed or not granted at all for several months, seven sources in the bullion industry in London, Hong Kong, Singapore and China said.

The journalist that wrote this didn’t consider the possibility “quotas have been … not granted at all for several months,” because Chinese banks didn’t submit for quotas. Most likely, when the price went up in May, Chinese demand declined and importing banks stopped asking for quotas. And merely stating that the PBoC blocked 300-500 tonnes because China imported 1,500 the year before is neither evidence nor an argument. The economy is a flux.

Only one week after the Reuters story, they came out with a follow-up, headlined “China eases restrictions on gold imports: sources.” Stating, “China has partially lifted restrictions on imports of gold, bullion industry sources said.” This second article was a bad attempt to back-pedal on their previous false analysis.

Still, because SGE premiums did rise somewhat in 2019 (mainly before May), some gold might have been obstructed from entering. But, in my view it can’t have been more than 50 tonnes.

In total China net imported 988 tonnes in 2019, down 34 year-to-year.