Denmark Releases Gold Bar List, But the Serial Numbers Are Missing

Written by Jan Nieuwenhuijs, originally published at Gainesville Coins.

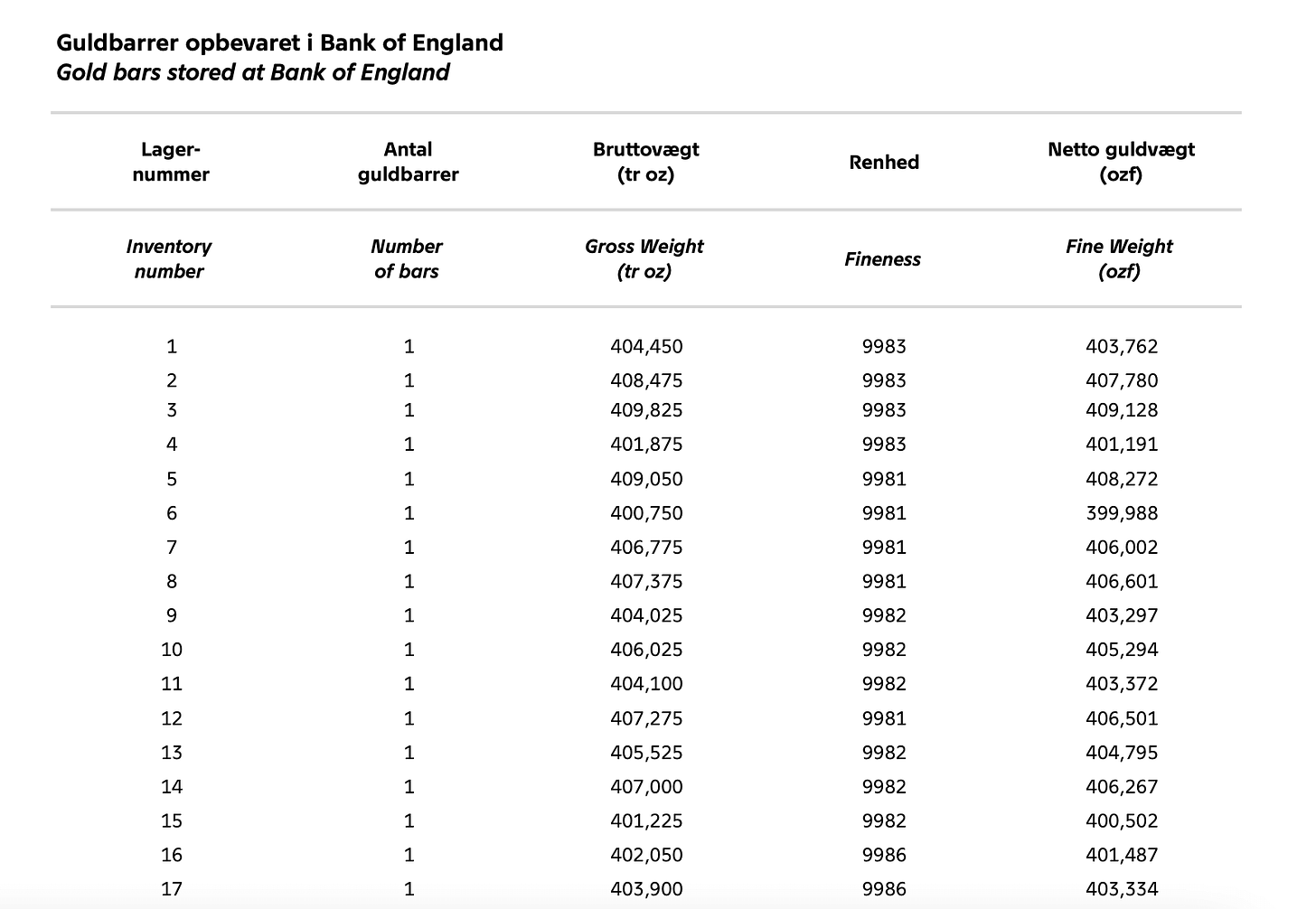

Late 2021 the central bank of Denmark released a bar list of its monetary gold. Unfortunately, the individual serial numbers of the ingots—the disclosing of which is the main purpose of a bar list—are missing. Government entities around the world have been increasing transparency regarding gold in recent years, but still have a long way to go.

Central Banks, Credibility, and Transparency

Credibility is a central bank’s most valuable asset. If credibility is lost, a central bank can close shop. Transparency is one of the means for a central bank to gain credibility. As monetary instability has been mounting for years, central banks are forced to become more transparent.

A central bank’s monetary gold can be viewed as its “Plan B.” If, for example, a central bank fails to control price stability through monetary policy (“Plan A”), it can peg its currency to gold to restore stability.

Gold is a sensitive topic, though. On one hand, a central bank needs gold reserves to underpin confidence in its balance sheet. Especially central banks that issue reserve currencies. On the other hand, if a central bank emphasizes gold too much, it could destabilize Plan A.

Central banks have a hard time finding a balance in how transparent to be about gold. Since 2008 the trend is more transparency, but not too quick. The following are examples of government bodies having increased gold transparency in the past fourteen years:

All major European central banks, except Banco De España (of Spain), have disclosed the geographic locations of their gold reserves.

Numerous central banks have been transparent about repatriating gold. Venezuela, Germany, and Austria announced repatriating in advance. Other countries, such as The Netherlands and Turkey, made it public after the gold was brought home.

Germany’s central bank has published an overview of its gold storage locations going back to 1950, through which we learned the Germans repatriated nearly 1,000 tonnes from London around the turn of the century.

Germany has published a book about its monetary gold reserves, released an eight-minute video of the vault in Frankfurt, and did an exhibition about its gold.

Russia’s central bank has released pictures of its gold reserves.

Central banks have started communicating about auditing their metal.

The Bank of England (BOE) has published monthly gold leasing data going back to 1999. I assume this refers to gold lent by HM Treasury (via BOE).

The U.K. has started publishing import and export numbers of non-monetary gold, revealing flows in and out of the largest gold market globally: the London Bullion Market.

Switzerland, the world’s largest refining hub, has published an excel sheet of the value and weight of non-monetary gold import and export per country since 1982.

China has started publishing non-monetary gold import and export data.

The U.S. has published a gold bar list of its monetary metal.

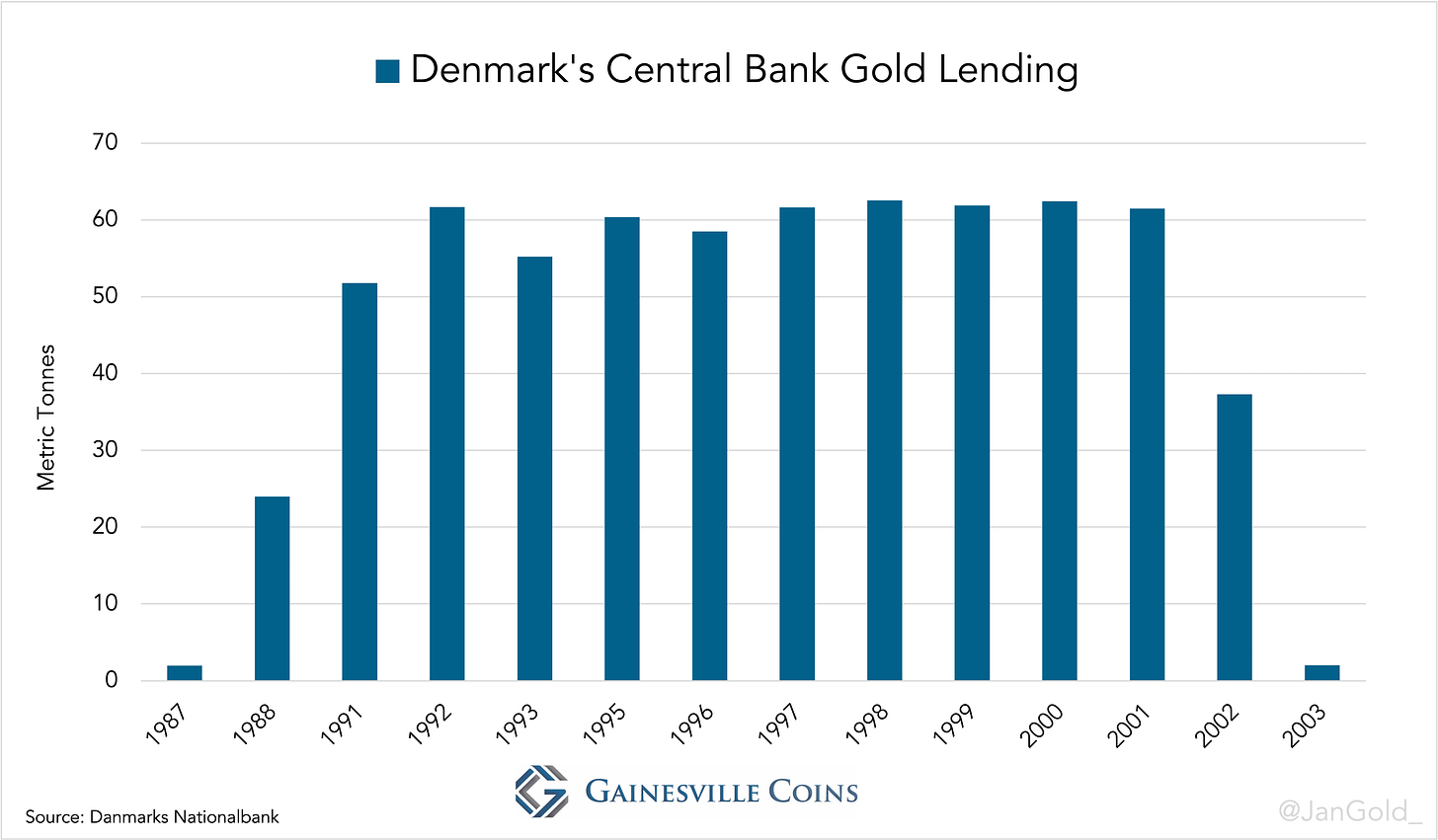

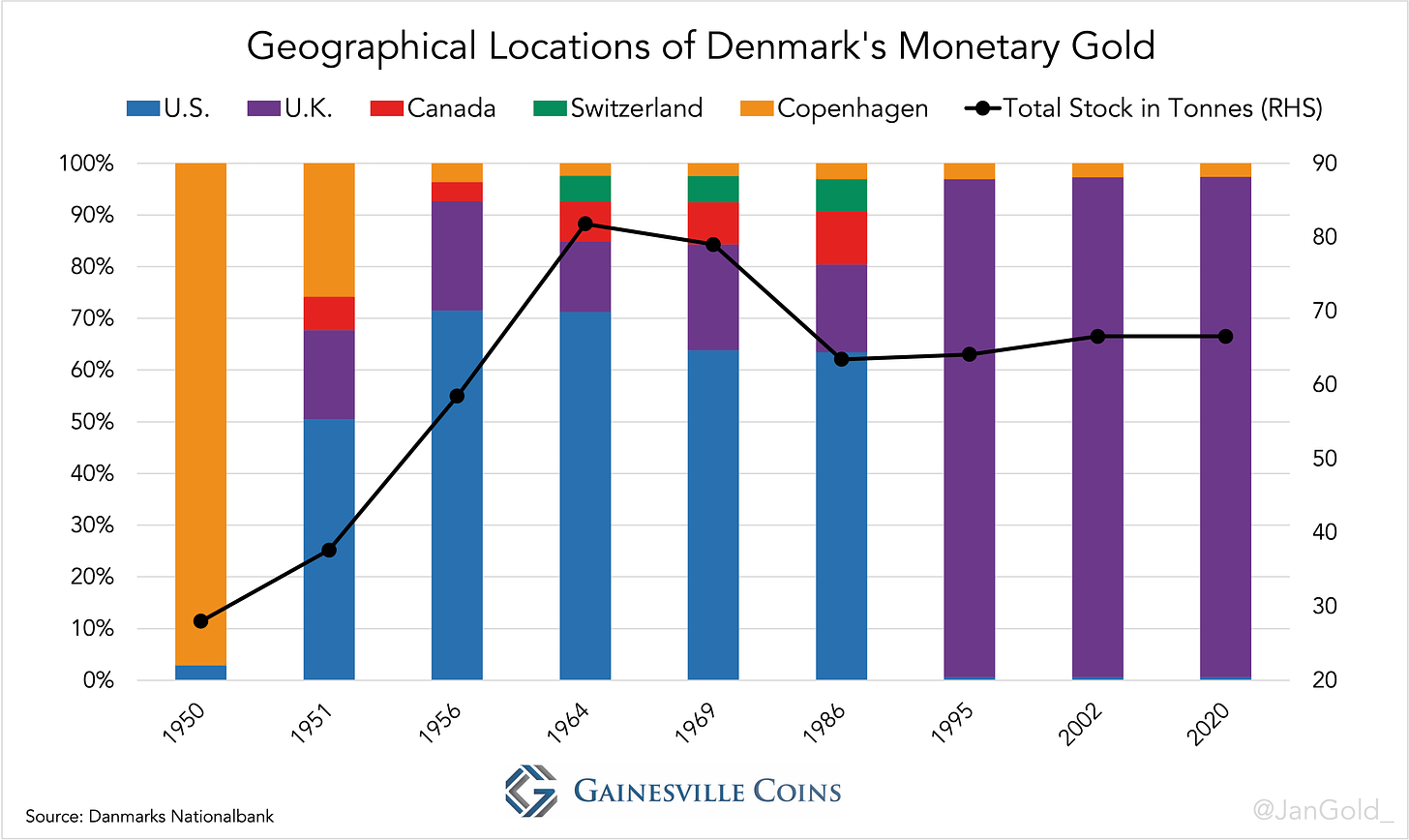

In October 2021 the Danish central bank released a report titled “Danmarks Nationalbank’s gold – a historical overview.” The report includes an historical background of the Danish gold, its storage locations since the Second World War, and how much was lent.

Currently, Denmark owns 66.5 tonnes of monetary gold. Of this total 0.5% is stored at the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, 2.5% is stored in Copenhagen, and 97% is stored at the BOE in London.

According to the report, Danmarks Nationalbank investigated to repatriate gold from London in 2010. It was decided not to repatriate “for the time being.”

We Need Full Transparency Regarding Gold

The gold report by Danmarks Nationalbank also covers “issues relating to … control and auditing of the gold stock.” In addition, a gold bar list was published. From the report:

After the Bank of England opened up the possibility of inspection visits, Danmarks Nationalbank carried out physical inspections in 2014 and 2018 at the Bank of England, where samples of the gold stock were checked. The registration numbers and purity of the sample of gold bars were checked by reading the stamp on the gold bars, which were also weight checked and ultrasound scanned. Ultrasound scanning is used to check that the individual gold bar is made of the same material throughout. The inspections did not give rise to any comments.

It's astonishing to read BOE didn’t allow audits, and foreign central banks didn’t push through for physical inspections, prior to 2014. By bringing up the subject of physical inspections, though, the Danes confirm the importance of audits. Crucial for a physical inspection is transparency, the involvement of an independent auditor, and all paperwork must be legit.

In the end the Danish taxpayers are the “shareholders” of Denmark’s central bank and the ultimate owners of its gold reserves. Danmarks Nationalbank is the custodian of the gold, which hires the BOE as a sub-custodian. In Danmarks Nationalbank’s Annual Report 2021 PricewaterhouseCoopers (PwC) shares its responsibility:

We are independent of Danmarks Nationalbank… We have conducted our audit in accordance with International Standards on Auditing and additional requirements applying in Denmark… In our opinion, the financial statements give a true and fair view of Danmarks Nationalbank’s assets, liabilities and financial position as at 31 December 2021…

I don’t know if PwC has physically verified gold at the BOE, but let’s assume the audit has been done as it should be.

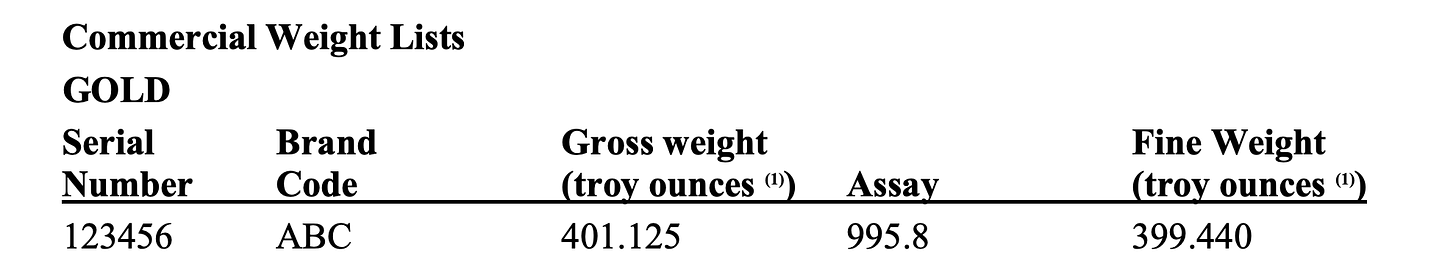

Now, about the bar list published by Danmarks Nationalbank, which doesn’t include serial numbers. The Good Delivery Rules for Gold and Silver Bars by the London Bullion Market Association (LBMA) prescribes a gold bar list to include a bar’s serial number, brand code, gross weight, assay, and fine weight. See below.

Danmarks Nationalbank must be in possession of such a bar list. On BOE’s website we read: “We only accept bars which comply with LBMA Good Delivery standards.” And the serial numbers of Good Delivery bars are documented by the BOE for its clients based on LBMA rules (see above).

Additionally, in the report it reads that Danmarks Nationalbank carried out physical inspections by comparing the “registration numbers [serial numbers on a list] … of gold bars” with the stamps on the gold bars.

As virtually all the Danish gold is stored at the BOE, where an additional 5,660 tonnes of other central banks and commercial banks are stored, we must be skeptical of the auditing procedures. We want to avoid bars at the BOE to be on Danmarks Nationalbank’s list, as well as on the list of other central banks.

If all central banks that store gold at the BOE—such as the central banks of Denmark, Australia, the Netherlands, Belgium, Germany, Finland, Italy, Portugal, Austria, Sweden, Switzerland, Romania, Poland, Japan, South Korea, and India—would publish a proper bar list, anyone can check if bars are listed twice. Next, the central banks should physically inspect their gold with independent auditors. This procedure would award full credibility for central banks. Credibility that might come in handy down the road.

To my knowledge only Mexico makes use of BOE storage facilities and has published a gold bar list with serial numbers. The gold bar list of the U.S. adheres to industry standards, but the Americans have no gold stored in London. The bar lists released of late by Denmark, Germany and Australia are next to worthless.

If Mexico can publish a proper gold bar list, why can’t others?

Correction: May 30, 2022: The Bank of Mexico has not released a proper gold bar list that complies to industry standards. The serial numbers on the list are not the same as the serial numbers on the bars. The list shows numbers from a shadow accounting system at the Bank of England.