Written by Jan Nieuwenhuijs, originally published at Gainesville Coins.

In Switzerland it’s a state secret where the central bank stores its gold domestically. From all the information I could gather I conclude the Swiss central bank primarily stores its gold—and that of foreign central banks and the Bank for International Settlements—on Bundesplatz 1 in the capital Berne.

This vault may be one of the largest globally. However, due to a renovation the vault is now empty. The metal has temporarily been transferred to a federal bunker near Kandersteg, deep in the Swiss mountains.

What led me to research this topic is a multi-year delay of a gold shipment by the Austrian central bank (OeNB) from London to Switzerland. From reading my previous article on this subject, some could be tempted to think OeNB’s gold is gone, or that the Bank Of England is obstructing the transfer. According to my analysis, though, London isn’t the problem. OeNB’s shipment was supposed to be in Berne by now, but due to a delay in the renovation of the vault the gold hasn’t been transferred yet.

To get to the bottom of this we will examine the vaults of the Swiss central bank in this article. In a following article I will present more proof of OeNB postponing to ship metal to the vault in Berne.

The first two chapters serve as an introduction. If you are short on time you can skip to the third.

The Swiss Have Been Digging Caves for Centuries

If there is one country that excels in building tunnels and caverns, it’s Switzerland. Berne was founded around 1200 on a peninsula in the river Aare. The peninsula is shaped as a hill due to the wear of the water. Enclosed by the Aare, the Old City could be easily defended by a wall at the West. The safety within this natural fortress allowed the city to flourish.

Many of the early inhabitants of Berne had vineyards outside of the city. Already in the 13th century cellars were being constructed below the buildings in the city, for more room and the right climate to preserve wine. The soil in Berne, consisting mostly of gravel and sand put there by glaciers during the last Ice Age, is well suited for constructing cellars. The weight of the ice caused the soil to compress*. Today, many of the cellars are being used as bars, restaurants, shops, and more.

Since 1983 the Old City of Berne is UNESCO world heritage site for its exceptionally coherent planning concept. Berne has always retained its historical character, presenting variations of the late Baroque period and Late Middle Ages. The Old City continues to be a place for living, working and commerce.

The first tunnel in Switzerland was built in 1707 to ease the passage over the Gotthard Massif Mountain in the Alps. Ever since, more road, railway, waterway, and maintenance tunnels have been built, by now totaling an astonishing 2,000 kilometers in length.

In the 1880s the Swiss started to build a line of fortifications in the Alps for the army to retreat and defend their country against a foreign invasion. In the Second World War a network of military tunnels and bunkers was added.

During the Cold War, in 1963, Switzerland undertook to provide bunkers for all citizen to take shelter in case of a nuclear attack. At one point, there were an estimated 300,000 fallout shelters. After the Cold War many of the bunkers in the Alps were considered obsolete. Some were reopened as hotels and museums, or found other uses.

Switzerland's Vast Gold Market

Switzerland is one of the largest physical gold markets globally. Not very much is known about it though, because discretion is one of the services that make this market attractive.

Before the 1930s banking secrecy was an unwritten rule in Switzerland. This rule was enshrined in legislation in 1935, which, together with political neutrality, made Swiss banks attractive for foreigner capital: currency, bank deposits, and gold.

When in 1968 the Gold Pool collapsed and the London Bullion Market closed for two weeks, Swiss banks reacted aggressively by trying to take over market share from London. Refining capacity began shifting from London to Switzerland. Currently, there are no London Bullion Market Association (LBMA) accredited refineries left in the U.K., while in Switzerland there are four giants: Valcambi, PAMP, Argor-Heraeus, and Metalor.

Every year roughly 2,000 tonnes of gold moves through the Swiss refineries, measured by non-monetary gold import and export.

Next to the vaults of the refineries, there are vaults of commercial banks**, secure logistics companies (Brinks, Loomis, Malca-Amit, etc.), and the Swiss central bank. In addition, after the Cold War several military bunkers in the Alps have been sold to niche vaulting companies that built storage rooms for precious metals and other valuables in the deep caverns.

There is no centralized gold exchange in Switzerland, so all trade is done over-the-counter. Because a few large Swiss bullion banks have their head office in the center of Zurich, an often used short-hand reference to the Swiss gold market is, “Zurich.” However, this can be misleading as not all physical trading is concentrated in Zurich. For example:

There are refineries in the far South of Switzerland and in the West.

Brinks has gold vaults in Zurich, Geneva, and Chiasso. Malca-Amit has vaults in Zurich and Geneva. Loomis told me it “can store gold all over Switzerland.”

Numerous other vaults can be found in old military bunkers in the Alps across the South.

Retail dealers and safety deposit boxes are all over the country.

Many watchmakers are in the West.

And, as we will see below, monetary gold is (normally) stored in Berne.

Officially, the domestic gold storage locations of the Swiss central bank (Schweizerische National Bank, SNB) are a state secret. In April 2013, SNB revealed 20% of its 1,040 tonnes of gold is stored at the Bank of England, 10% is at the Bank of Canada, and 70% is held domestically “in its own vaults.” Questions in parliament about the domestic storage locations are not answered for security reasons. Regardless of the locations of the vaults, SNB does confirm it stores gold for foreign central banks.

The Swiss Central Bank’s Main Gold Vault Is in Berne

There is a considerable amount of evidence that most of SNB’s gold has always been stored in Berne. An important source I have used for my research is a book published by SNB in 2012, celebrating the 100th anniversary of their head office in Berne. The title of the book is, “Die Schweizerische Nationalbank in Bern Eine illustrierte Chronik” (DSN hereafter).

When SNB was erected in 1907, it was decided to build two head offices to distribute the balance of power. One in Berne, the political center and capital of Switzerland, and one in Zurich, the financial center. SNB was divided into three departments of which Department I and III settled in Zurich. Department II in Berne took responsibility for all issues relating bank notes, the management of gold reserves (the receipt, dispatch and storage of gold bars and coins), and dealings with the federal administration.

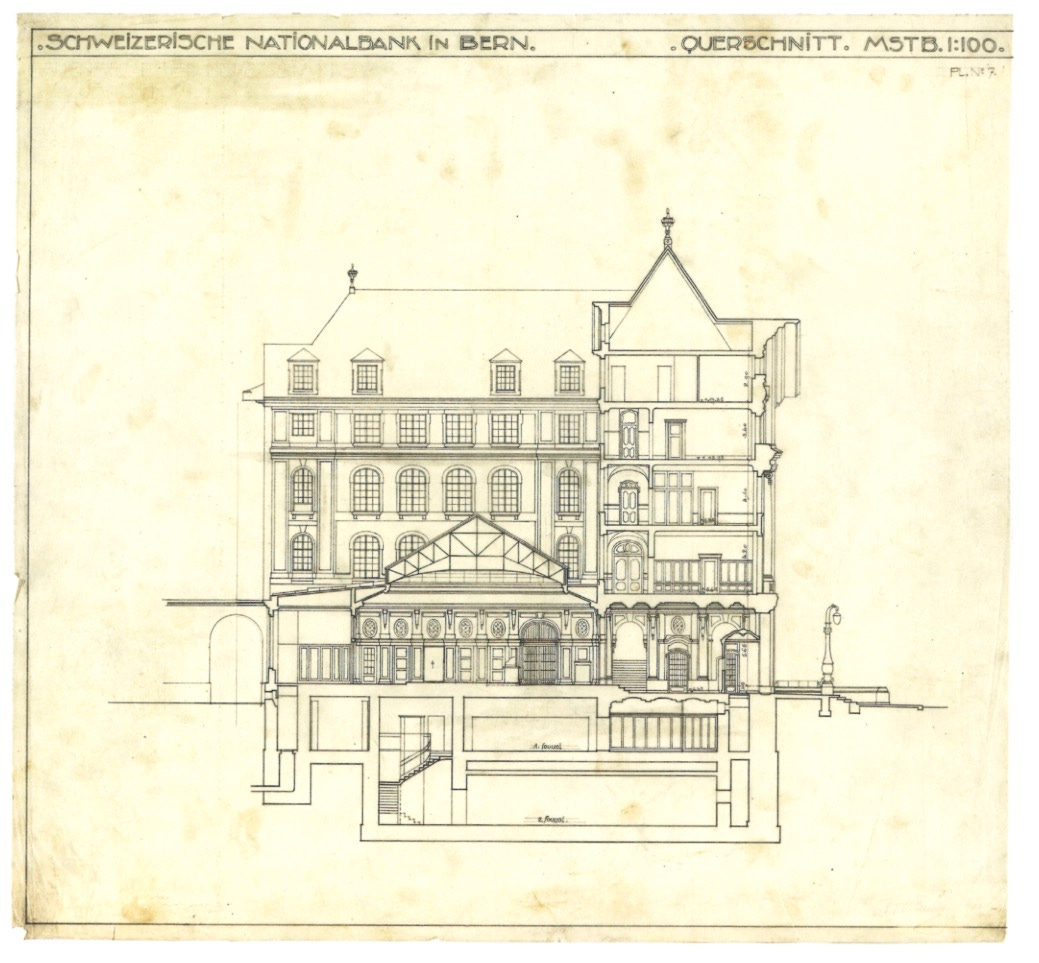

The head office in Berne at Bundesplatz 1, with its gold vault in the basement, was completed in 1912. It’s located in the Old City next to the Federal Palace that houses the Federal Parliament and Federal Council.

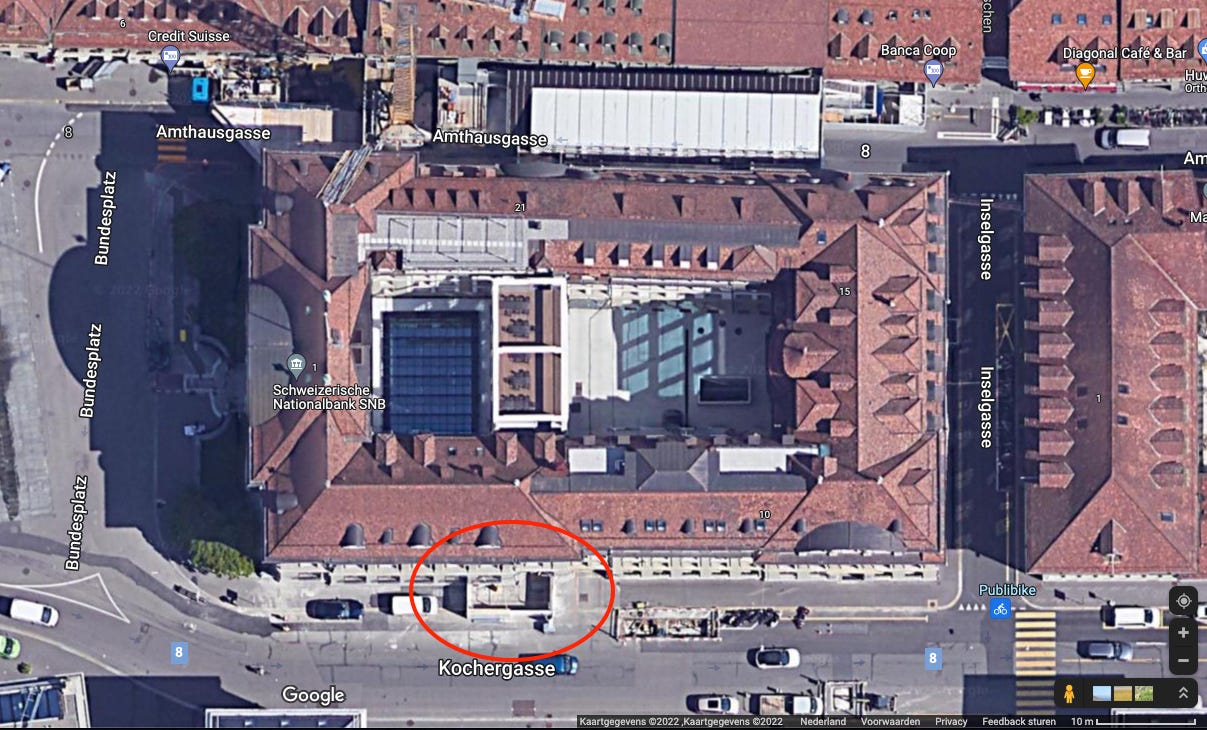

After SNB established itself on Bundesplatz, it attracted commercial banks with political as well as financial interest to the area. On Google Maps it shows SNB is still surrounded by commercial banks. Having banks in close proximity can have eased SNB’s gold dealings in Berne.

Until and through the Second World War, Berne retained its standing as a monetary gold hub. In the 1990s, a commission investigated SNB’s role in World War II regarding gold dealings with the German central bank (Reichsbank). The final report discloses that during the war many central banks had used SNB’s vault. The following tables show the Reichsbank’s deposits at SNB, and to which entities the Reichsbank sold. Clearly, these deposits and trades were done at the SNB vault in Berne.

During and after the Second World War, SNB’s gold reserves went up significantly. What’s not mentioned in DNS is that shortly after the war the main building went through two renovations.

In 1946, the first basement floor was modified, according to the building archive of the city of Berne. No details of the renovation are publicly available, but given SNB’s gold reserves were swelling and the vault was in the basement of the building, we may assume the vault was renovated. In 1951 and 1952 an underground air raid shelter (luftschutzkeller) was constructed. The same architect that renovated the vault in 1946, Otto Brechbühl, was hired to build the shelter.

But did he built a shelter, or add extra floors to the vault?

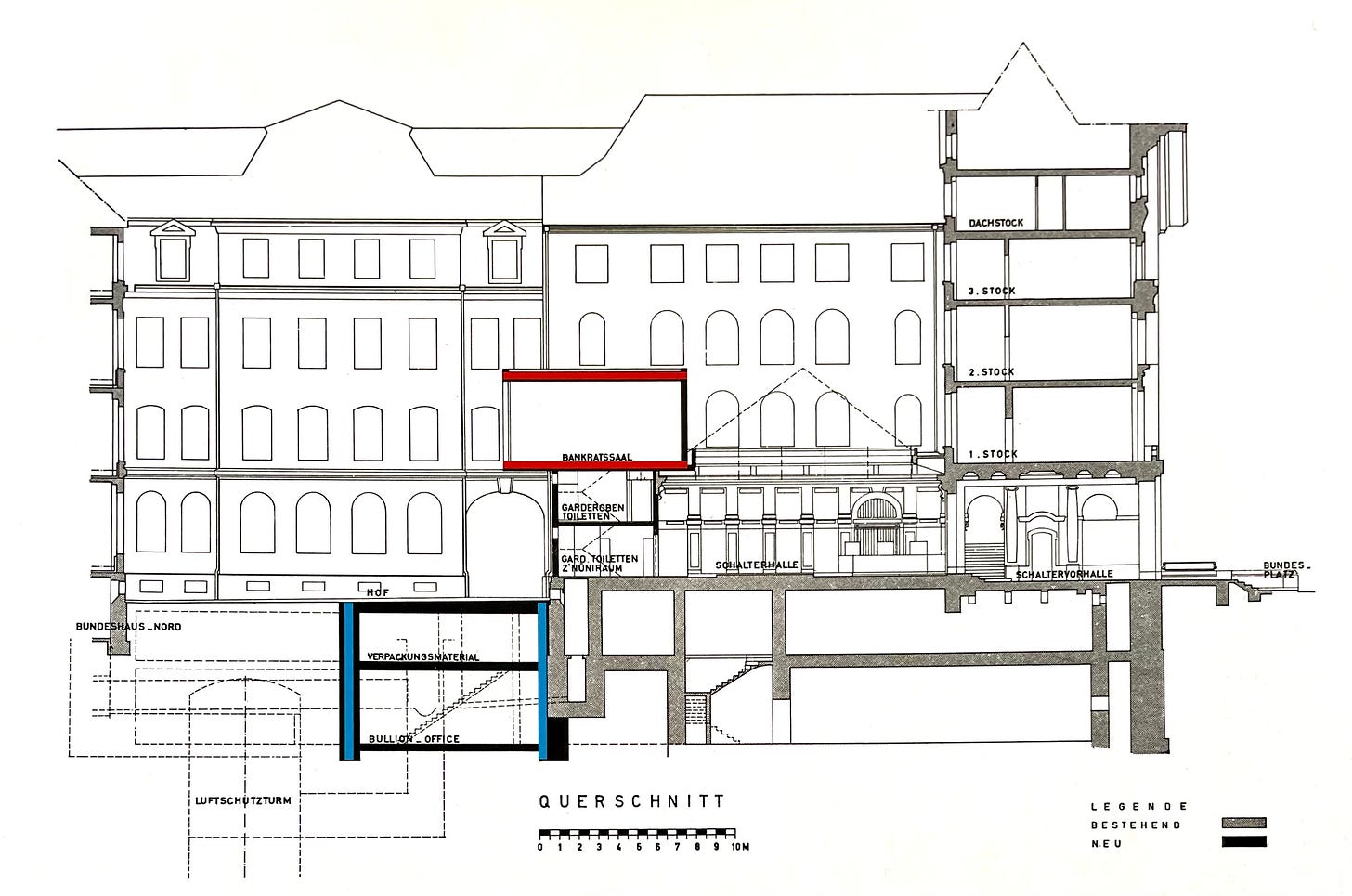

The authors of DSN state Department II was in need of space in the 1950s. “New safes were installed in the early 1950s,” they write, which could refer to Brechbühl’s work. In the late 1950s, “the main cash desk also requested an underground bullion office between the main building and the Bundeshaus Nord [the building on the east side of the main building where SNB rented offices] for shipping and packaging the gold.”

The authors of DSN, of course, cannot be fully truthful. Security details and other information about the vault must be concealed.

Above is a drawing of the building from 1960 taken from DNS. It displays the main building on the right, a segment of the Bundeshaus Nord on the left, and (in blue) the newly planned bullion office. We can also see the shelter (luftschutzturm) in dotted lines.

In the drawing the shelter is labeled as an “air raid tower.” The word “tower” implies there are multiple floors. Interestingly, the lower compartments of the shelter have no floor, indicating the drawing is incomplete. So why doesn’t the drawing show the entire shelter? Why is the shelter more than 15 meters deep? Why is only the shelter drawn in dotted lines? What’s so special about this structure?

According to DNS the bullion office was constructed from 1961 until 1963, a renovation which isn’t recorded in the building archive of the city of Berne. The reason why both records are incomplete is secrecy. I tried to obtain plans, drawings, and building permits from the renovation in 1946, 1951–1952, 1961–1963, and all others that followed, from the building archive and SNB’s own archive. Without exception I was told all documents are classified as “SECRET” or “sensitive,” and can’t be viewed.

Most likely the dotted lines in the drawing above don’t show a shelter, but the entrance from the bullion office to a vault consisting of several floors stretching out beneath the old basement and beyond.

For a fact the vault is larger than what’s shown on the drawing from 1960. In 2018 Bluewin journalists managed to view drawings from Berne’s geoinformation department. Below is a screenshot of the video showing a plan of Bundesplatz. An expert concludes SNB’s basement stretches out about 10 meters underneath the square. No (public) record reveals the basement has been enlarged underneath the square. What else has been omitted?

A retiree named Othmar Dillon, who used to work at Berne’s cadastral survey (Amtliche Vermessung), told newspaper Der Bund he had been inside the vault on Bundesplatz 1 multiple times since the 1970s. He saw the gold there. According to Dillon the vault reached down the level of the river Aare, which would imply it’s 40 meters deep in total. Depending on the number of floors built, and the sharpness of Dillon’s memory, the gold vault could be up to 10,000 square meters.

The article from 2008 quoting Dillon was lost from the internet but Der Bund gave me approval to republish it (download here). I checked with Berne’s resident’s database and Dillon does indeed exist. Sadly, I haven’t been able to contact him.

Other sources substantiate the vault on Bundesplatz 1 is sizable. In 2013 a journalist from SRF was allowed to film SNB’s monetary gold. Below is a screenshot of the video that was published.

The video is highly likely from inside the vault on Bundesplatz 1, and not some other vault. Photographer Martin Ruetschi was allowed to enter SNB’s vault in Berne in 2001 (after pushing for ten years). If one compares Ruetschi’s pictures (see below) with the video, they both show the same racks for the gold and the same floor tiles. Removing more doubt is a copy from Ruetschi's series in DNS.

Ruetschi said he was “led through a long labyrinth of corridors and finally through the thick vault door” before he could take the pictures. That sounds there are more than two floors in the basement.

The forklift in SRF’s video reveals there must be a heavy-duty elevator down to the vault. Forklifts themselves can weigh up to several tonnes because they use counterweights for the load they carry on the fork. Observing the latest drawing from 1960 and recent images from Google Street View makes me think there is an elevator near the entrances for armored trucks on the south side of the building, leading down to the bullion office and floors below. Right about where the “shelter tower” is.

The forklift also confirms this is a large and active vault, storing gold not only for SNB but also for foreign central banks and the Bank for International Settlements (and Swiss bank notes).

On the website of the Bank for International Settlements (BIS), they state they offer central banks, “gold location exchange, safekeeping and settlement: loco London, Berne or New York.” The reference to a vault in Berne, which the BIS uses since the 1930s, must be at Bundesplatz 1.

In the 1970s, SNB continued expanding its presence on Bundesplatz. In 1971 it bought a property north of the main building: the Kaiserhaus. Due to stringent planning codes in the Old City, SNB had to think of a construction concept in line with the city’s aesthetic and functional needs, as well as its own. It was decided the ground and first floor of the Kaiserhaus were rented to shops. The upper floors could be used for offices and other purposes. A basement was also constructed. “The most difficult work was in the basement,” the authors of DNS write.

There is a photo of a tunnel connecting the main building and Kaiserhaus on page 90 of DNS. The floor of the tunnel looks to be covered with soft plastic, though, which is not suited for a forklift. I don’t think there is a gold vault underneath the Kaiserhaus.

Kandersteg’s Federal Bunker

In 1999 Swiss journalists discovered that the government had arranged a classified command facility near Kandersteg in the Alps, 40 miles south of Berne, to hide during a nuclear attack. Since 2004 the exact coordinates of the facility are publicly known.

For nearly two decades not a word was written about any gold being stored at the bunker dubbed “K20.” Then, in 2018, independent journalist Henry Habegger reported K20 also incorporates an SNB vault. People familiar with the matter shared with Habegger that when K20 was built, SNB took the opportunity to acquire a nuclear bomb-proof vault for its gold reserves. K20 has room for 6,000 tonnes of gold. The people that live in Kandersteg have often seen armored trucks driving through, escorted by army vehicles in full gear, including machine guns.

According to my analysis, all gold inside the vault in Berne has been moved to Kandersteg but will return within a few years. Here’s why.

In February 2015 an extensive construction project began to renovate SNB’s main building and the Kaiserhaus in Berne. At the time of writing, the main building is finished (everything above ground), but the Kaiserhaus construction is still ongoing. Below are images of the renovation from Google Street View, Maps, and Earth taken in 2017 and 2022.

A white fence is visible around the Kaiserhaus (at Amthausgasse) and in front of one of the entrances for armored trucks on the south side of the main building. Together with other evidence, this tells me the vault is out of service.

One, a Swiss journalist that helped me during my research—he prefers to stay anonymous—spoke to one of SNB’s directors at a media dinner in 2016. Regarding the renovation the director told him that, “you can assume that the gold is at a secure place.” He was told the gold was moved out for the renovation.

Two, in 2015, the Austrian court of audits stated OeNB—then and now storing 6 tonnes of gold in Switzerland—would have limited access to audit its metal in Switzerland due to renovation work at the depository until 2018. Afterwards the renovation audits could take place normally. The earliest projections by SNB were that the renovation would be finished late 2018. (In a following article I will show more evidence OeNB’s 6 tonnes in Switzerland is currently at an SNB vault, and another 50 tonnes is destined to an SNB vault.)

Conclusion

It can’t be a coincidence that OeNB has limited access at its SNB vault in Switzerland, Bundesplatz 1 is renovated around the same time, and a story about an active gold vault in Kandersteg pops up in Swiss media around the same time as well. Normally, OeNB’s gold, other foreign central banks’ gold, the BIS’s gold, and most of SNB’s gold is at Bundesplatz 1, but due to the renovation it was moved to K20.

I conclude SNB prefers to keep most of its gold in Berne, because historically this is the main vault. After the Second World War, when SNB’s reserves ballooned, vaults could have been built anywhere in Switzerland, still SNB decided to enlarge the vault at Bundesplatz.

Furthermore, the fact OeNB’s gold in Kandersteg will be returned to Berne, tells me SNB’s own gold will be returned as well (or at least what was stored in Berne previously). Why return OeNB’s gold but not the Swiss gold? If the vault in Kandersteg, mind you it can hold 6,000 tonnes, was superior to the one in Berne, SNB could have told OeNB the vault was moved permanently. New custodial contracts could have been signed, and the Austrians could have been granted full access to audit their gold in Kandersteg. But that’s not what happened. Not in 2015 when the renovation in Berne started, and not in 1999 when K20 was completed.

Can it be SNB also has a vault in Zurich and in other places? Yes. There is just very little evidence any of these vaults play a significant role in storing metal belonging to SNB, foreign central banks, and the BIS. Needless to say, I will report accordingly if I find new evidence.

The renovation in Berne is now set to be completed in 2024. Then, or just before, the gold can be returned to Bundesplatz 1. OeNB will have normal auditing access, and it will send another 50 tonnes to Switzerland.

Any remaining blanks and questions will be addressed in my following article (“Why Austria’s Monetary Gold Transfer to Switzerland Is Delayed”) here on Gainesville Coins.

Notes

* Information on the history of Berne’s cellars I have mostly based on private communication with archeologist Armand Baeriswyl, Lecturer in Medieval and Modern Archaeology at the University of Bern.

** Several commercial banks have vaults in the center of Zurich, such as Zürcher Kantonalbank and Bank Julius Baer, that store gold to back ETFs (source: Ronan Manly from Bullionstar). There are also large gold vaults near Zurich airport in a bonded warehouse. Two commercial banks that have their head office in Berne, Valiant Bank and Berner Kantonalbank (BEKB), have disclosed to have underground vaults below their buildings at Bundesplatz, though these appear to be mainly used for safety deposit boxes. From Berner Zeitung in 2020 (Google Translate):

The two Bern banks, Valiant and Berner Kantonalbank, also have their headquarters on Bundesplatz in downtown Bern. The vaults with the customer's lockers are located in the basements of the two banks, as Valiant spokesman Marc Andrey and BEKB spokesman Florian Kurz say.

This intel is golden! Excellent report.

great in depth analysis.