How the physical gold price is set, and how physical and derivates markets around the world are connected and interact.

Founding Members of The Gold Observer may submit a topic for an article. One of the first Founding Members was Marko Viinikka, who asked me to write an article about how the global gold market operates and how the physical gold price is set. An excellent topic! How can we ever understand gold if we don’t know how the global market functions?

Introduction

The price of physical gold is set by supply and demand for physical gold. The global physical market can be divided into exchange trading and bilateral trading. In addition to the physical market there are multiple gold derivate markets that influence the physical market. To understand the entire machine, we will examine the workings of gold exchanges, bilateral trading (networks), and derivate markets separately, and finally how all derivatives are tied to the physical market. Derivatives are traded on exchanges and on a bilateral basis as well, but for the sake of clarity we will discuss them independently.

Important to mention is that there is not one physical gold price. As gold is a commodity and the forces of supply and demand for commodities are not equal at any and all locations—and energy and time are needed to transport commodities—the price of physical gold differs geographically. Moreover, physical gold comes in many shapes, weights and purities. Manufacturing costs for bars are more or less fixed, but relatively cheaper for larger bars due to their higher value.

What most people refer to as the spot gold price is the price per fine troy ounce of gold, derived from trade in large wholesale bars located in London (“loco London”). Large wholesale bars weigh roughly 400-ounces. The smaller a bar compared to “large bars,” the higher the premium it will attract. Gold coins and jewelry enjoy even higher premiums per fine weight, due to even higher manufacturing costs. The “real price of physical gold” thus depends on where you are and what type of product you are trading.

A gold product’s fine weight is calculated as:

Fine weight = gross weight * purity

Gold Exchanges

An exchange is a centralized market. On any exchange multiple gold contracts can be listed. On the Shanghai Gold Exchange, for example, spot gold contracts varying in size from 100 grams to 12.5 Kg are traded. Supply and demand on an exchange meets through the exchange’s order book. Simplified, some market participants submit limit order bids (buy) and asks (sell) in the order book, while others submit market orders (buy or sell). A matching engine connects and clears all orders and this is how the price is set.

Because the order book is visible to all traders and there is a central authority that sets the trading rules, exchange trading is more transparent than bilateral trading networks called over-the-counter (OTC) markets. Some traders prefer exchange trading, some prefer OTC trading that offers more flexibility and discretion.

Spot gold exchanges are sparse. Examples are the Shanghai Gold Exchange in China, the Borsa Istanbul in Turkey, and the Dubai Gold and Commodities Exchange in the U.A.E.

Arbitrage causes prices between different parts of the global gold market to synchronize. When gold is cheaper in Dubai than in Shanghai an arbitrager can make a risk-free profit. The classic example is that the arbitrager will lock in his profit by buying the gold where its cheap and physically transports the metal to where it’s more expensive to sell. If the trade is profitable depends not only on the price spread, but also on the costs of financing (interest), shipping, insurance, and possibly the recasting of bars. Alternatively, the arbitrager can take a long position on one exchange and a short position on the other until the spread has closed, and exit his positions.

Generally, gold trades at a discount in net exporting countries, such as South Africa, versus a premium in countries that are net importers. Gold trading hubs like the U.K. can flip from a net importer to a net exporter, which will cause the local price to trade at a premium or discount versus parts of the world that are on the other side of the trade (usually Asia).

Bilateral Trading

In the previous chapter we discussed that globally there are only a few physical gold exchanges. Implying, the majority of physical gold trading is done bilaterally: negotiated on a principal-to-principal basis, whether that be through an electronic trading system, by phone, or face to face.

Because gold doesn’t perish and has been highly valued for millennia, all gold that has ever been mined is still with us. This makes gold trade more like a currency than a commodity in terms of supply and demand dynamics. Physical supply and demand are anything but restricted to annual mine output and newly fabricated products.

Every day, gold is traded on a bilateral basis between thousands of companies—refineries, banks, dealers, mints, miners, jewelers, industrial fabricators, investment funds, etc.—and perhaps millions of individuals around the world. Gold can be exchanged in any form, and of course it can be altered in shape, weight and purity throughout the supply chain.

At the smallest level a bilateral trade can be a Turkish woman selling a golden bracelet to her male neighbor. By agreeing to her offer price, the neighbor affects the global price of gold, albeit extremely little. For, if the neighbor would reject the woman’s offer, she would sell the bracelet to a jewelry store that is connected to the global gold market where supply would increase. Accepting her offer causes supply not to increase. Through this example it’s clear that with every (bilateral) trade buyer and seller influence the gold price.

Business-to-business trading in a bilateral trading network is referred to as an OTC market. Globally, the London Bullion Market, overseen by the London Bullion Market Association (LBMA), is the most dominant gold OTC market. Another vibrant OTC market is in Switzerland, which is the gold refining capital of the world. Each year, hundreds to thousands of tonnes of gold supply are transported to Switzerland, where 400-ounce bars destined for London, 1 Kg bars destined for Asia, 100-ounce bars destined for New York, or other bars and products are manufactured depending on demand. Switzerland also accommodates many large vaults for gold investors.

The London Bullion Market has a unique framework because it’s based on bilateral trading, yet it has a centralized character. We will discuss this market in the next chapter on derivatives, because most trades in London are executed through “paper contracts.”

Derivate Markets

A derivative is a “a type of financial contract whose value is dependent on an underlying asset.” In this article we discuss derivatives with physical gold as the underlying asset. The single most important difference between physical gold and a derivative of gold, is that owning physical gold doesn’t incur any counterparty risk, whereas owning a gold derivative does. For other commodities, like corn, it can be said: “you can eat corn, but you cannot eat a corn derivative.” It boils down to the same economic conclusion: physical supply can’t be increased by the creation of derivatives.

Yet derivatives have a considerable impact on the physical gold price, as they trade in large volumes and many use leverage. In my view, the most relevant derivates markets are the paper market in London, Exchange Traded Funds, and the futures market in New York.

The LBMA’s Chain of Integrity and the London Bullion Market

The London Bullion Market is an OTC market so there isn’t a rulebook like with an exchange. However, this unique market is to an extent organized. Let’s start with the basics.

Globally, there are 71 LBMA accredited refineries, which are the gate-keepers of the LBMA’s chain of integrity. These refineries strictly accept gold from reputable sources, and when supply is cast into bars weighing in between 350 and 430 troy ounces, having a fineness of no less than 995 parts per 1000, they adhere to the LBMA’s Good Delivery standards. The chain of integrity is a closed system of refineries, secure logistics companies, and custodians that ensure all metal within the chain is of the quality it’s supposed to be. Bars withdrawn from the LBMA’s chain of integrity can only re-enter through the accredited refineries.

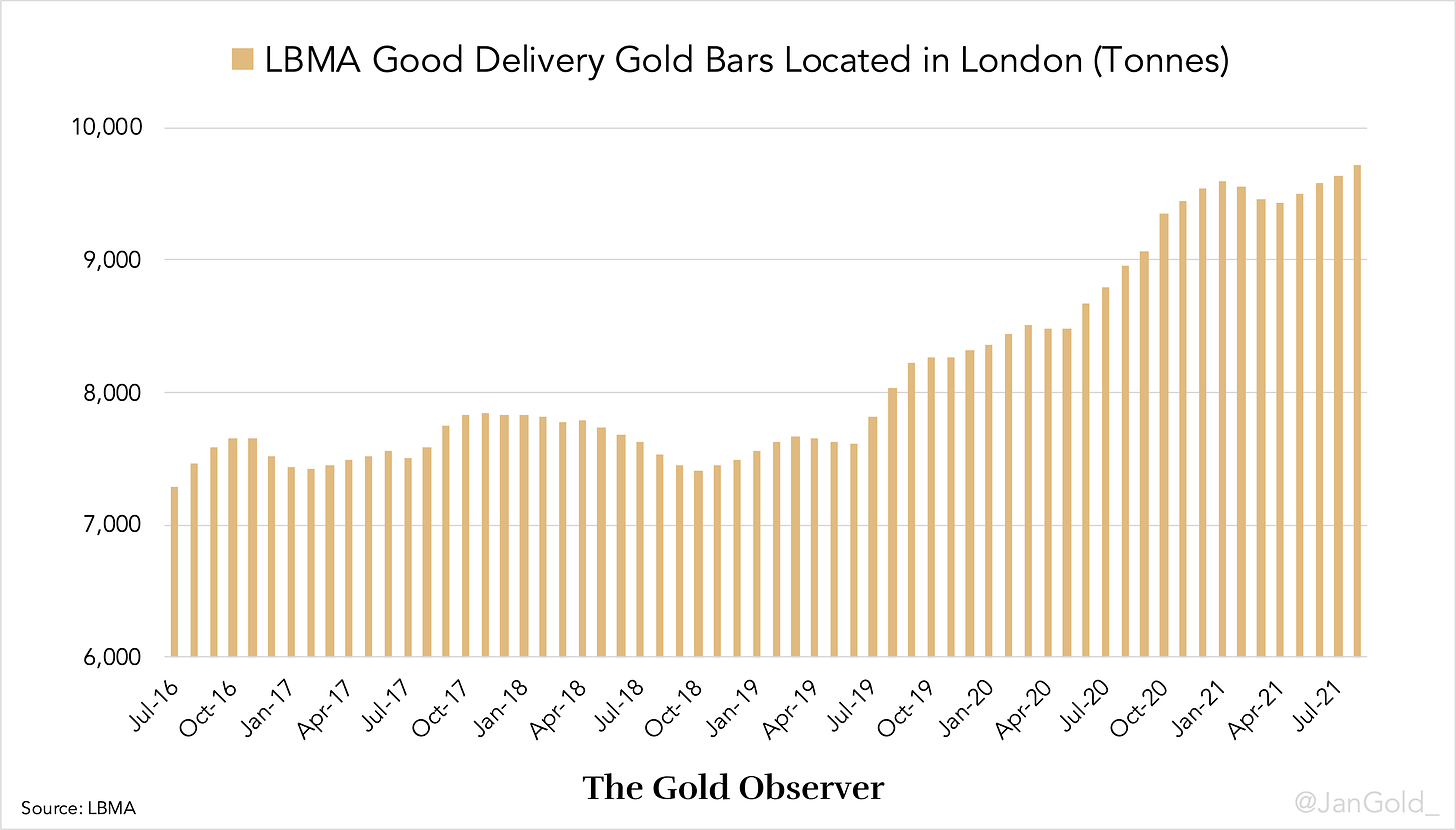

LBMA member secure logistics companies may transport large bars to vaults located within the M25 London ringway. When stored in the London vaults the bars are now London Good Delivery, and underpin trade in the London Bullion Market. Although the gold is located in London, traders from all over the world participate in the London Bullion Market, as we will see in a minute.

Keep in mind that the system of vaults in London must not be confused with the LBMA’s chain of integrity. The chain of integrity spans the globe and also includes bars with divergent weights from LBMA Good Delivery.

Gold bars produced by LBMA accredited refineries are the global standard. The Shanghai Gold Exchange (SGE), as an example, accepts gold bars from SGE certified refineries in its vaults, next to LBMA certified metal.

AURUM and Global OTC Trading

At the heart of the London Bullion Market is an electronic clearing system called AURUM, which connects the LBMA member clearing banks. The London Bullion Market can be seen as a gold banking system with physical gold located in London as reserves, and AURUM as the clearing house.

Trading gold in London is mainly done on a spot unallocated basis. An unallocated account at a bullion bank is a claim on a pool of physical gold owned by the bank. Holding an unallocated balance (in short, “unallocated”) can be compared to a fiat deposit at a regular bank. Unallocated is the credit in the London Bullion Market.

In contrast, through an allocated account at a bullion bank a customer owns uniquely identifiable bars that are set aside, and are not on the balance sheet of the bank. Customers pay storage fees for holding allocated metal, versus much lower costs, if any, for holding unallocated. Any customer is allowed to switch from unallocated to allocated, and vice versa, which connects the paper market with the physical market in London. Bullion banks have agreed that any fee for “allocating” metal can only be changed on a 30-day notice.

The main reasons why the majority of trading in the London Bullion Market is done on an unallocated basis are convenience and efficiency. What makes gold special is that it’s both a commodity and a currency. Trading on an unallocated basis makes it possible, for example, to buy gold for exactly $1,000,000 U.S. dollars, or borrow exactly 25,000 ounces. The size of an allocated trade is always tied to varying bar weights, which leads to inconvenient numbers. This is why “loco London unallocated” is used as the primary currency in the global OTC gold market.

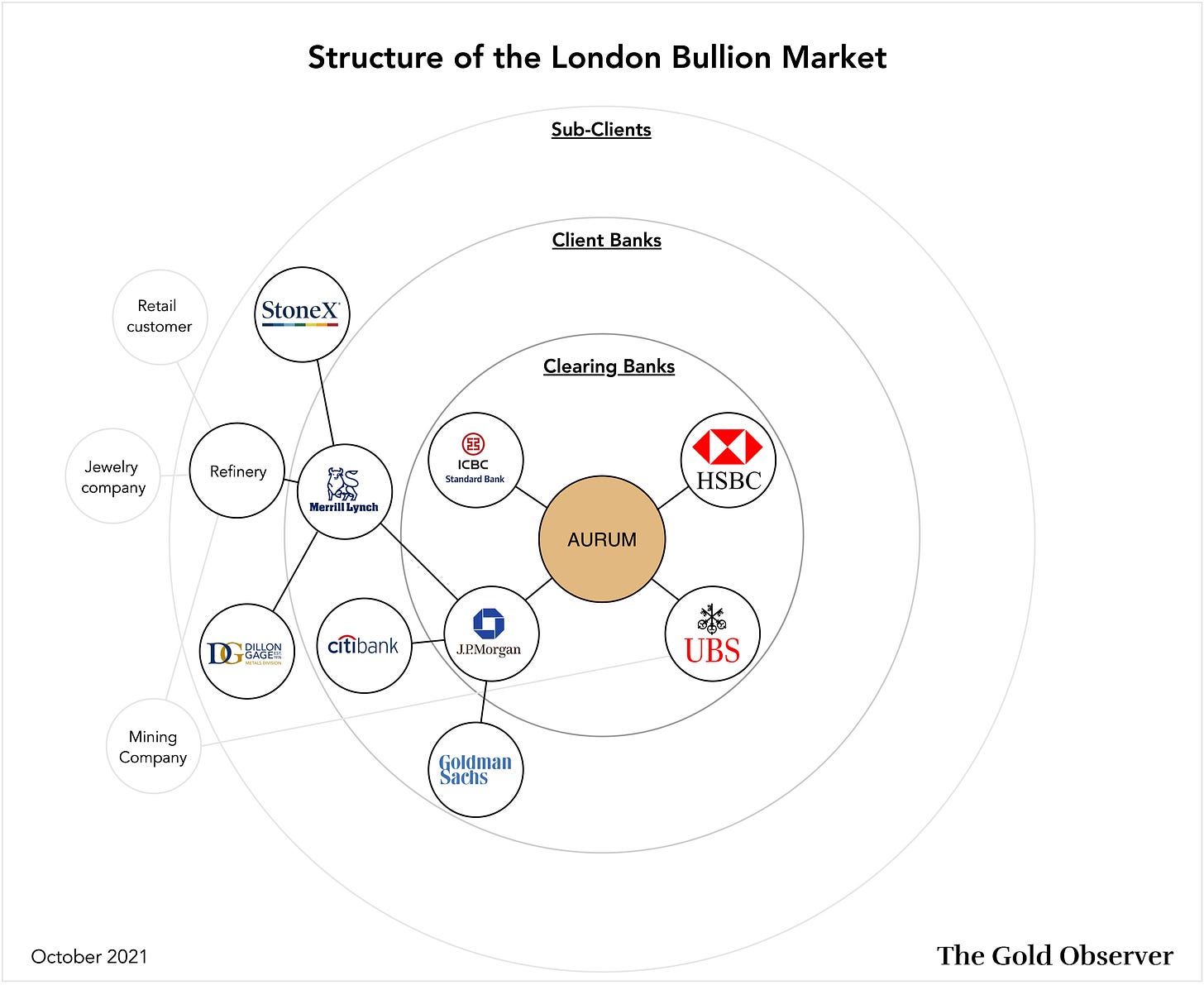

Clearing through AURUM is overseen and managed by London Precious Metals Clearing Limited (LPMCL). The clearing banks that take part in AURUM (the LPMCL members) are HSBC, ICBC Standard Bank, JP Morgan, and UBS. Other banks and participants in the London Bullion Market are in one way or another connected to the clearing banks.

Clearing banks either have their own vault in London, have an account with custodians such as Brinks or Loomis, or use the Bank of England’s vault.

So, how does the actual trading work? Suppose, a gold mining company borrows 180,000 ounces of unallocated, at an interest rate of 2% from a bullion bank in London it has an account with. The bank is UBS, which happens to be a clearing bank. After receiving the loan, the miner sells the metal spot to use the proceeds for a mining project in Australia. A year later the miner has mined 183,600 ounces and wants to repay UBS the principal plus interest (assuming the interest was agreed to be paid in gold). The miner transports the unrefined gold to a refinery in Australia and indicates it wants to be paid in loco London unallocated. The refinery accepts the gold and instructs its bullion bank in London, Merrill Lynch, to transfer 183,600 ounces from its own account to the miner’s account at UBS (see the above graph for clarification). Merrill Lynch will inform its clearing bank JP Morgan regarding the transfer of 183,600 ounces to the miner’s account at UBS. When UBS has received the unallocated through AURUM, the miner’s account will be debited by 183,600 ounces and the loan is repaid.

What is settled in Australia are the cash costs for refining the gold, and a correction for the local gold price discount/premium versus the price in London.

If any physical gold is transferred between JP Morgan and UBS through AURUM depends on all trades of these banks and their clients. In the London Bullion Market thousands of unallocated trades are executed on a daily basis, causing the clearing banks to have many claims on each other at the end of each day. The clearing procedure starts each day at 4:00 PM GMT with the LPMCL members “netting out” all claims. After this process is exhausted the residual claims are settled in physical gold.

Another example of how gold is being exchanged in the London OTC market is companies, central banks, and investors trading gold like they trade any other currency in foreign exchange markets. On a spot basis, but also through forwards, swaps, options, and leasing.

The LBMA Gold Price Benchmark

Trading in the London Bullion Market is done between all LBMA members. But with so many participants you may wonder what is the spot gold price in this market? Technically, in this web of trading there is not one price of gold.

At the core of this market there are 12 LBMA market making members that are required to quote a two-way (bid and ask) market throughout the day. These quotes are only accessible for entities that have an account with these banks. The spot gold price you see on, i.e., Bloomberg, Reuters or Netdania is often an amalgamation of several feeds from LMBA market makers. As a consequence, prices can slightly differ across said media.

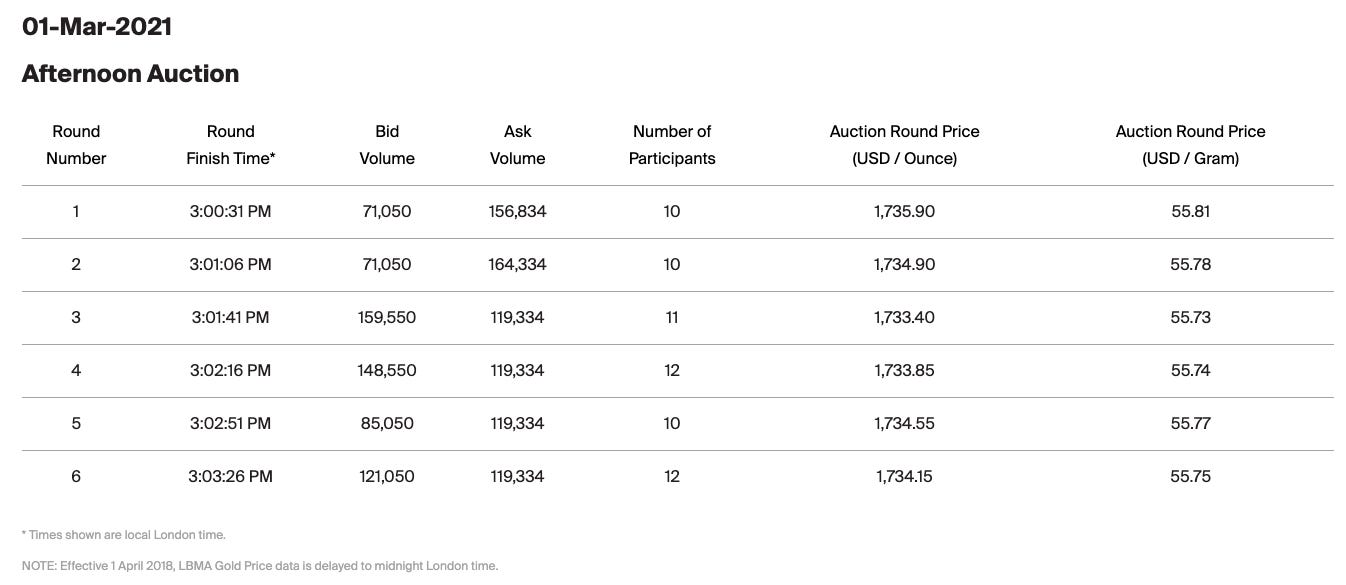

Which brings us to another feature of the London Bullion Market: the LBMA Gold Price benchmark. Previously named the London Fix, the LBMA Gold Price is an auction held twice a day: at 10:30 AM and 03:00 PM. It’s used for a variety of purposes in the global market, such as industrial contracts.

There are 16 registered direct participants in the LBMA Gold Price, all of which can provide access to the auction for clients. An auction begins with the announcement of a starting price. Based on the starting price, the direct participants and clients present if they are buyers or sellers and in what quantity (loco London unallocated). Typically, after the first round the buying and selling volumes of all participants are not in equilibrium, and the price is adjusted up or down, followed by a new round of bidding. The process is repeated until the net volumes of all participants fall within the pre-determined tolerance. Finally, the metal is settled and the auction price is published.

The above is a simplification of the London Bullion Market. For more information, please refer to the LBMA OTC Guide and visit the LBMA website.

For researching the workings of the London Bullion Market I have consulted with industry insiders Bron Suchecki, Ross Norman, and Jeffrey Christian. Any inaccuracies in this article remain my responsibility.

Exchange Traded Funds

Exchange Traded Funds (ETFs) are funds backed by commodities, stocks, derivatives, or other financial assets. Shares of ETFs are traded on a stock exchange. Commonly, gold ETFs are backed by physical gold. The largest gold ETF is GLD with a current inventory of roughly 1,000 tonnes in London Good Delivery bars. Buying a share of GLD does not provide ownership of physical gold, but a slice of ownership in the Fund. GLD caters exposure to the price of gold without leverage. Investors choose to invest in ETFs, because they are regulated financial products and easily accessible through brokers.

One GLD share represents roughly 0.1 ounce of gold. This amount decreases over time because the storage fees are subtracted from the assets (gold) held by the Fund.

The price of GLD is connected to the physical market, because a select group of arbitragers, called the Authorized Participants (APs), can create and redeem GLD shares at the Fund’s Trustee BNY Mellon Asset Servicing. If, due to supply and demand of GLD shares, the GLD price falls below the spot price in London, the APs can buy GLD shares and redeem them at the Trustee for physical metal which they can sell at a profit in the spot market. Consequently, GLD inventory will decrease. Should the price of GLD rise above London spot, the APs do the opposite: buy spot metal and create GLD shares to sell in the stock market. When shares are created the APs must deposit gold in the allocated account of the Trustee (“All of the Trust’s gold is fully allocated at the end of each business day”). As a result, GLD inventory increases.

Through arbitrage GLD and the physical market interact and influence each other.

The Futures Market

A futures contract is an agreement between two parties to exchange a commodity (or stock index, bond, etc.) for cash at a specific price at a fixed date in the future. Although, the majority of commodity futures contracts never reach physical delivery—most are “rolled over” or terminated before expiration. Futures contracts involve leverage and are used by hedgers and speculators.

Futures are traded many months into the future, but for this article we will focus on the “near month” contract, which captures the bulk of trading volume. Hereafter, I will refer to the price of the near month contract simply as the futures price.

The most traded gold futures contract is GC, listed on the COMEX futures exchange in New York. Similar to GLD, gold futures interact with the spot market through arbitrage. Because London is the most liquid spot market, this is where most arbitragers will trade versus New York.

Say, the futures price transcends London spot, to an extent that arbitragers can profit by buying spot and sell short futures. Surely, the arbitragers can allocate metal in London, recast large bars into 100-ounce bars, fly it to New York, and physically deliver the futures contract when it expires. However, in reality this will rarely happen. Unless there is, in example, a pandemic that derails global flights, arbitragers will take a long position in London and sell short futures in New York, wait until both markets converge and close their positions. Needless to say, when the spot price is higher than the futures price, arbitragers will do the opposite: short London and buy long futures.

The futures market, too, is connected to the physical market through arbitrage.

Worth mentioning is that when a futures long (short) position is rolled to the next near month, and the initial buying (selling) caused an arbitrager to buy (sell) spot in London, on a systemic level the arbitrager will roll its position as well. In this sense, London serves as a warehouse for the COMEX.

Conclusion

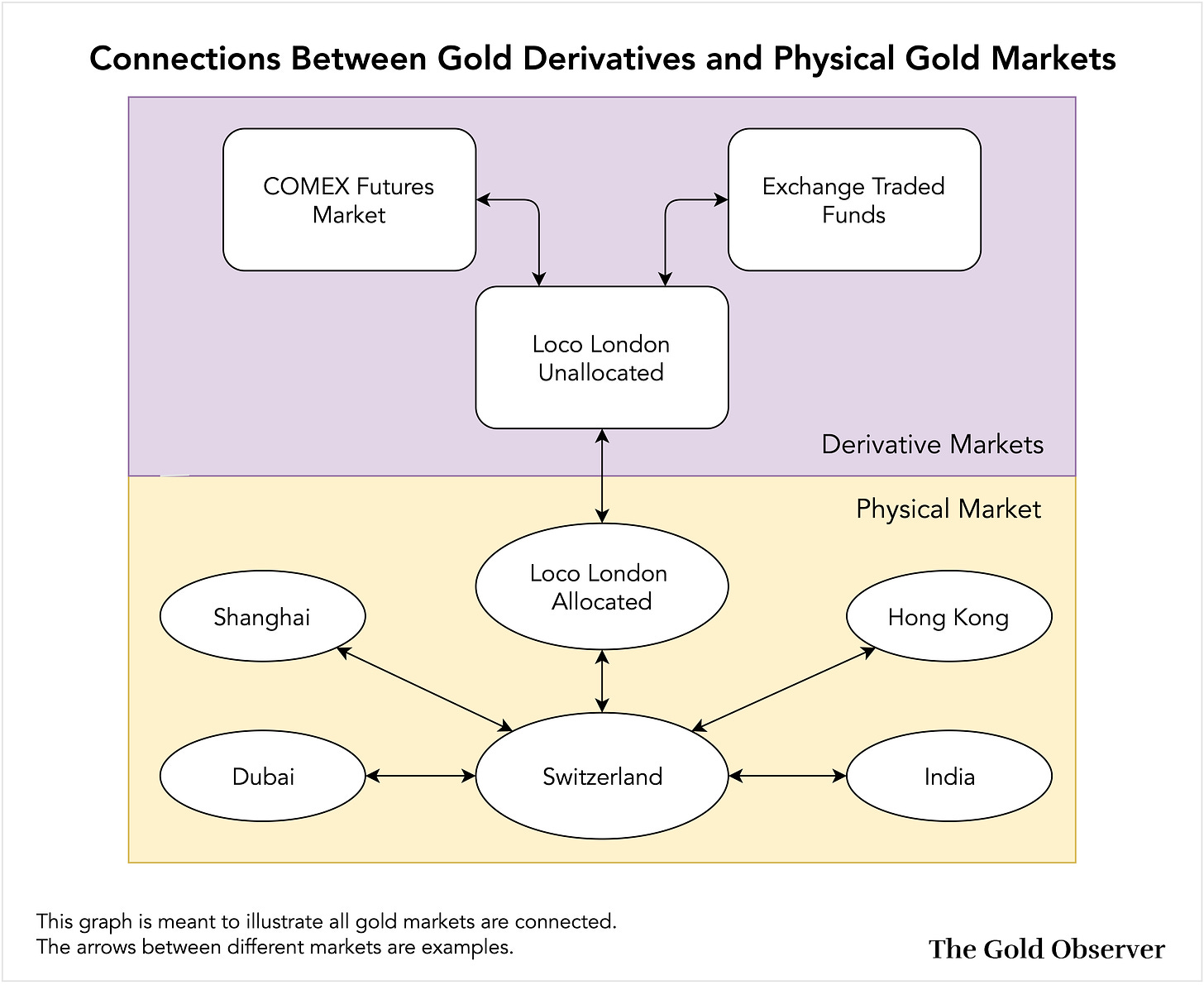

Below you can see a graph that shows how GLD and the futures market are connected to the physical market in London, and how London is connected to the rest of the world. Effectively, all gold markets are connected.

The price of physical gold is set by “regular traders” in the physical market, and arbitragers that trade physical gold versus derivatives. Hence, I wrote in the introduction: “the price of physical gold is set by supply and demand for physical gold.” Gold derivatives can be seen as an extension of the physical market. Measuring the impact of derivatives on the physical market falls outside the scope of this article, but I have planned a discussion on this subject.

I took the opportunity to make this “article on request” part of my series Gold Market Essentials. Previous articles in this series are:

Upcoming articles in this series will be more detailed discussions on the workings of the futures market, bullion banking, and the London Bullion Market.

If you enjoyed reading this article please consider to support The Gold Observer and subscribe to the newsletter.